The Greenhouse Effect - Technical References & Backup

The numbered references here refer to numbers * in the section "The Greenhouse Effect For Laypersons"

1. Photon Flux

A photon is the smallest possible packet of energy of light and other electromagnetic radiation. It has no mass or electric charge and travels at the speed of light. The energy of a photon is directly related to their frequency or wavelength (speed of light divided by frequency). Higher frequencies correspond to higher energy photons.

A stream of these photons moving through the atmosphere is called ‘flux’. Photon flux is more specifically defined as the rate at which photons pass through a specific area per unit of time.

2. GHGM: Greenhouse Gas Molecules

Greenhouse gas molecules include the most important Greenhouse gas which is water vapour (H₂O).

Other GHGMs occurring in trace amounts in the atmosphere include carbon dioxide (CO₂), Methane (CH4), Nitrous Oxide (N2O), and Ozone (O3).

There is a large suite of other GHGMs, largely non-natural human pollution, that occur in tiny amounts including, for example sulphur hexafluoride (SF6).

3. TOA – Top of the Atmosphere

TOA is mainly used as a convenient term for what might be seen by satellite coming from the ‘top of the atmosphere’. More specifically, it refers to the Exosphere, the outermost layer that gradually fades into space, with no hard boundary.

4. Spectral Band

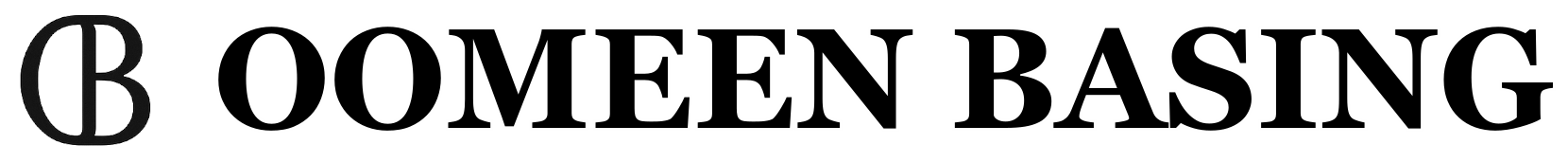

Is a concept used by spectroscopists to define areas in an absorption (or emission) spectrum that deviate from the background – usually in a bell-like shape.

The diagram shows how at low concentrations the band grows significantly as concentration increases. Bands 1, 2 and 3 show how the band increases to the point where the peak reaches level where all the available photons are absorbed.

Once this ‘Saturation’ peak is reached absorptiononly grows by broadening – as indicated by band 4.

5. Complex Spectral Signatures: carbon dioxide and water

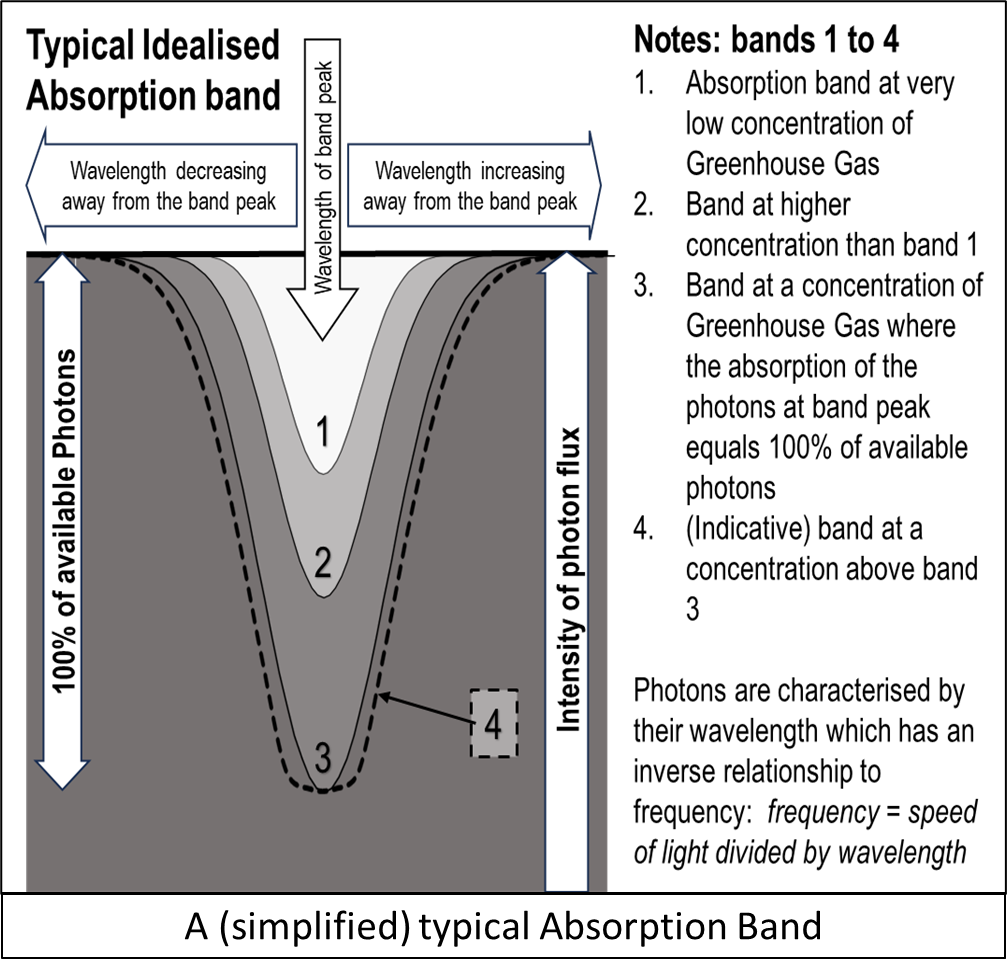

The absorption spectra exhibited by all GHGMs are complex and made up of very many bands that resemble the Spectral Band discussed above.

The complexity may be emphasised by considering the estimates of absorption coefficient – by frequency – of water and carbon dioxide.

These absorption bands give rise to the spectrum that can be observed from space.

6. Schwarzschild’s Radiative Transfer Equation

Karl Schwarzschild, the German physicist and astronomer, the first to exactly solve Einstein’s field equations of general relativity providing the radius of a black hole which became known as the Schwarzschild radius. He studied radiative transfer (energy transfer via electromagnetic radiation) through a medium in local thermodynamic equilibrium that both absorbs and emits radiation.

His fundamental equation of radiative transfer through a medium with absorbing / emitting molecules (i.e. the atmosphere containing greenhouse gas molecules) – is given by equating the incremental change in spectral intensity (the radiant intensity per unit wavelength measures in Watts per steradian per metre squared per frequency)

{N x XS x ( BB(frequency, T) – Intensity entering)}

over an incremental distance

It relates how much intensity of radiation changes as it passes through an incremental distance (think here as it passes through a metre of the atmosphere as it makes its way from the surface of the Earth towards space).

It is dependent on the parameters:

N: the number density of absorbing/emitting molecules (units: molecules/volume) – i.e. abundance

XS: the absorption cross-section at the particular wavelength under consideration (units: area)

BB(frequency, T): the black body radiation at the frequency in question and the temperature of the incremental distance being considered.

Intensity Entering: is the intensity of radiation, at the particular frequency in question, entering the incremental distance.

This fundamental equation underlies all theoretical calculations aimed at estimating the magnitude of the greenhouse effect.

7. Vibrational Excitation

Molecular vibration is a periodic motion of the atoms of a molecule relative to each other, such that the centre of mass of the molecule remains unchanged.

Vibrations of polyatomic molecules such as water (H2O), Carbon Dioxide (CO2) and Methane (CH4) are described in terms of normal modes, which are independent of each other, but each normal mode involves simultaneous vibrations of different parts of the molecule. In general, a non-linear molecule has many modes of vibration.

A greenhouse gas molecule becomes excited when the molecule absorbs the energy of a suitable frequency photon. Suitable photons, for any particular molecule’s absorption ‘peak’ fall into a narrow wavelength band.

A fundamental vibration is evoked when a suitable photon is absorbed by the molecule in its ground state. When multiple photons are absorbed, the first and possibly higher overtones are excited.

Simultaneous excitation of vibration and rotations gives rise to vibration–rotation spectra.

When a molecule has absorbed a particular frequency photon it can readily emit the same frequency photon in a process spectroscopists call ‘relaxation’.

The emission probability is linked to the temperature of the emitting molecules. This gives rise to the BB(frequency, T) term in the Schwarzschild radiative transfer equation.

The absorption probability for any particular frequency photon by a greenhouse gas molecule is determined by two factors “N & XS” the number density and the absorption cross-section.

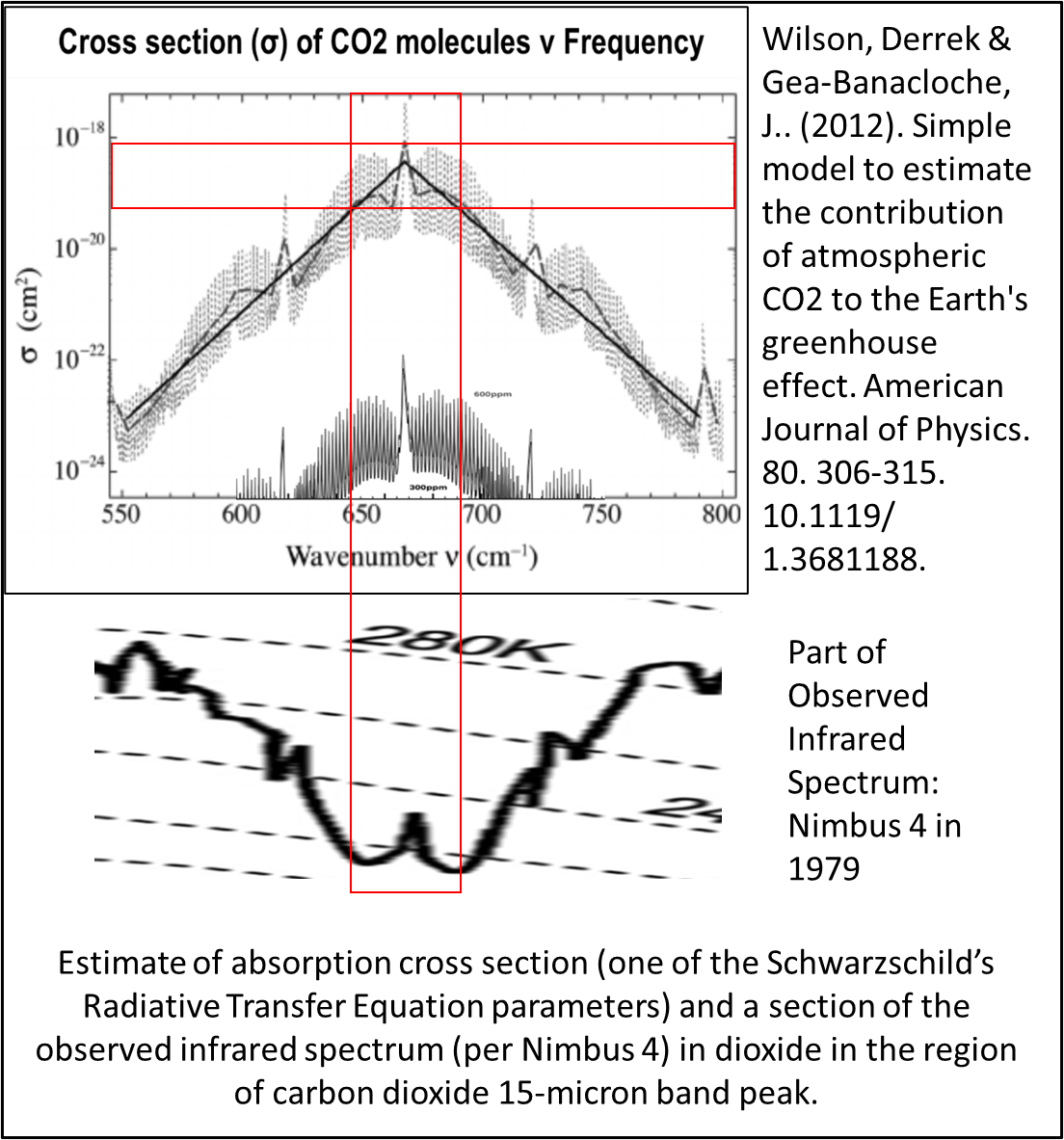

The estimate of the cross section may be compared to the observed spectrum showing how they align.

The red boxes show that the ‘Saturation’ zone for carbon dioxide occurs from peak cross section down to about one fiftieth or sixtieth of peak. This indicates that the peak, centre of carbon dioxide’s band becomes saturated around 5.5 to 6.8 ppm of carbon dioxide.

8. Effective Density

The two factors from 6. Schwarzschild’s Radiative Transfer Equation: number density and the absorption cross-section may be combined for all GHGMs at a particular frequency and position in the atmosphere by summing the number density times the absorption cross-section.

The number density is also referred to as abundance and is the number of molecules in a given volume. It is concentration as adjusted by pressure.

As in the previous note, it can be seen that absorption cross section falls off rapidly – more or less as the natural log of the distance away from the band peak.

When effective density for a particular frequency is negligible from the Earth’s surface to the TOA, there is no interaction of the photons with GHGMs, and those photons escape through the ‘window’.

Where the effective density exceeds a certain threshold all the way from the surface to the start of the Stratosphere, then the condition for ‘saturation’ is met. Carbon dioxide that has similar atmospheric concentration at all altitudes. The calculation above (Note 7) indicates that saturation occurs at the start of the Stratosphere at about 6ppm so that at the surface it occurs at 1.5ppm.

Note that this is relevant for the peak of the absorption band. Other lesser absorbing peaks (with lower absorption cross-sections) will hit saturation at higher concentrations of carbon dioxide.

9. The window

As discussed above the concept of ‘the window’ is a zone of frequencies where the effective density of all GHGMs is negligible.

In this window zone there may be minor absorptions occurring but scattering by atmospheric particulates may also take place. It is, therefore, not a ‘crystal clear window’.

However, for Clear Skies about 30% of the photons leaving the surface escape through the window.

The concept also comes into play when the effective density falls below the threshold for saturation and some of the photons begin to escape unabsorbed.

This concept is important in Effective Emission Altitude further discussed in note 11.

10. Planck Black Body Radiation

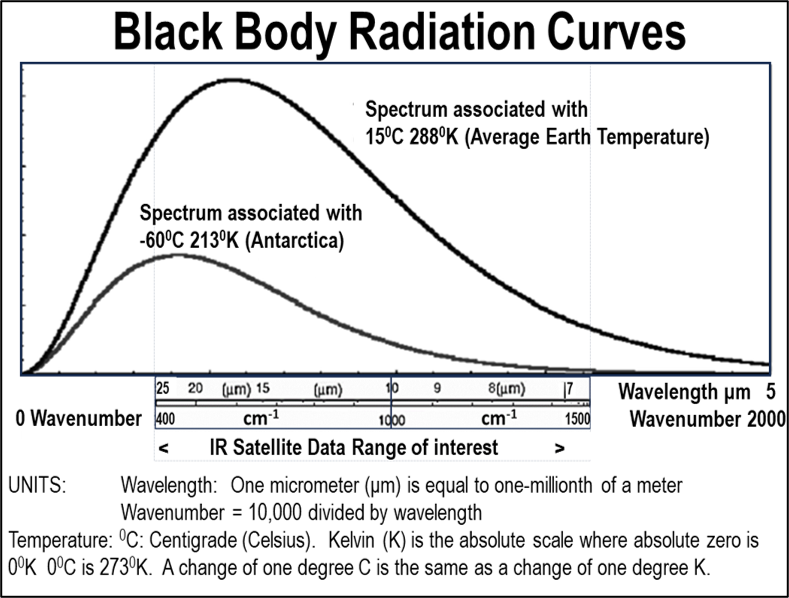

Developed by Planck and Wien towards the end of the nineteenth century a black body is considered a perfect absorber and emitter of radiation. A very hot body (like the sun) emits high-energy shortwave radiation while a warm surface, like the Earth, emits longwave radiation in the Infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum.

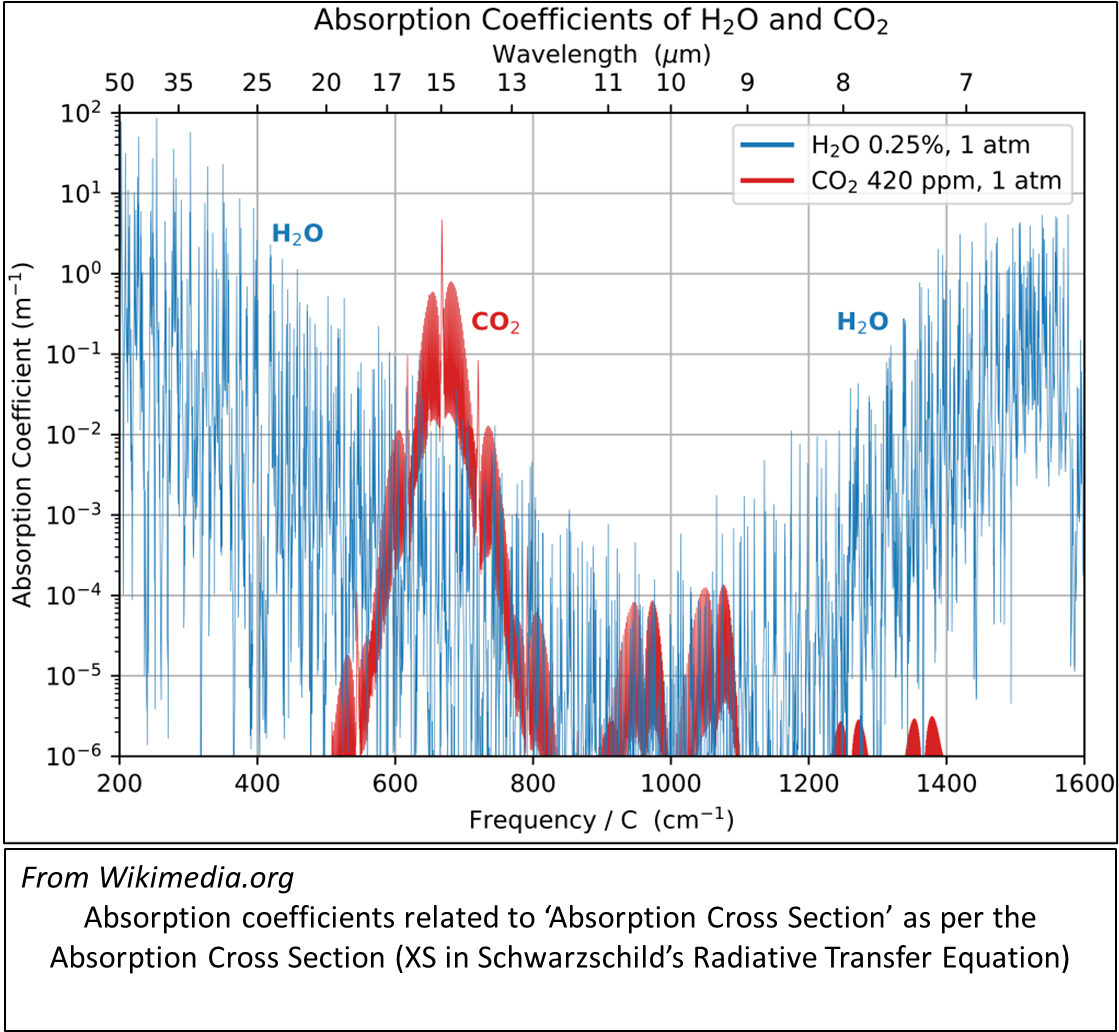

If there were no absorption (and emission) of Infrared radiation through the atmosphere an infrared satellite would observe a near-perfect black-body spectrum from the section of the Earth’s surface it was currently pointed towards.

The Stefan-Boltzmann law provides a means of calculating the magnitude of emissions from the surface of the Earth. It is a fourth power law and a cold surface (like antarctica) warming by one degree will increase emission by about 2% a hot surface at 50⁰C warming by one degree increases emission by ~1.2%.

The whole effect can be approximated by averaging the global surface temperature increase which, in going from 14⁰C to 15⁰C increases emissions by 1.4%. For the whole surface of the Earth that adds ~5.5Wm-2 (watts per square meter of Earth’s surface) to the surface emissions.

11. Effective Emission Altitude

Where effective density is over the saturation threshold all the way from the surface to the Stratosphere, the Greenhouse effect – at that frequency – is defined by two temperatures: the emitting surface of the Earth and the Stratosphere where temperatures stop falling. The contibution to the total Greenhouse effect at that frequency is not increased if concentrations increase - the frequency is 'Saturated'

Where the effective density tails off to below the saturation threshold before reaching the region where temperatures stop falling (Stratosphere), some photons begin to escape through a 'window'. This raises the temperature of the emissions as seen by an observing satellite.

This temperature can be ‘read off’ spectrographs where the peak absorption begins to ‘tail off’ (see graphic in note 4).

This effective temperature is equivalent to an effective altitude.

The zone betwen 'Saturation' and 'Window' is the ‘overlap and broadening zone’. This is the focus of the Clear Skies theoretical calculations aimed at quantifying the incremental Greenhouse effect due to elevated Greenhouse gas concentrations.

Where the effective density is near-negligible throughout the Troposphere, the Effective Emission Altitude is surface (ground or sea) level.

12. The Stratosphere & Atmospheric Layers

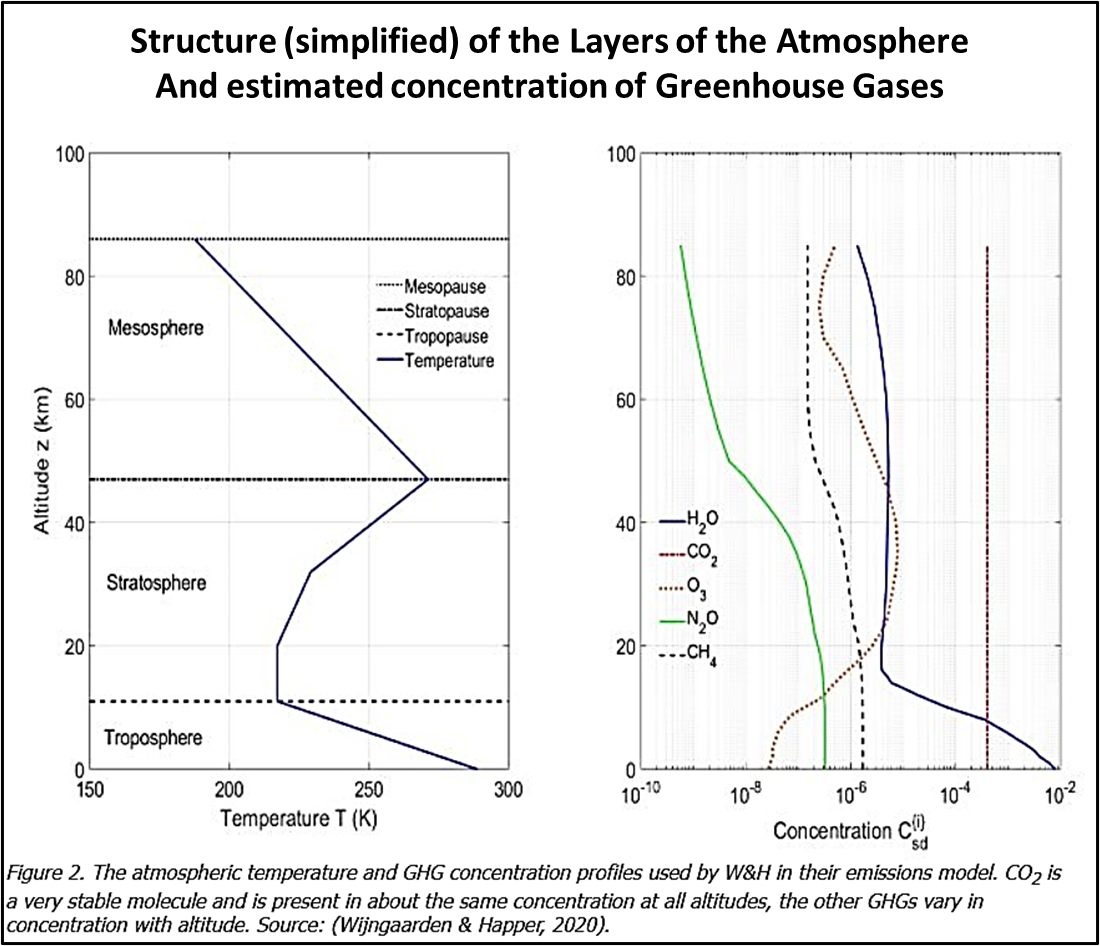

The figure (taken from Wijngaarden and Happer’s 2020 paper) illustrates the layers, their temperatures and GHGM concentrations.

Temperatures in the Troposphere fall until the Stratosphere is reached. The fall is not even throughout the Troposphere due to effects like turbulence and inversion.

After a steady, flat temperature zone in the lower Stratosphere, temperatures rise – as seen by emissions from these warmer zones of carbon dioxide and ozone.

By the time the mesosphere is reached effective densities of all GHGMs is near-negligible.

Concentrations of GHGMs other than ozone and carbon dioxide fall off rapidly with altitude – note that the graph is on a log-scale.

Carbon dioxide retains an even concentration throughout while ozone follows a complex profile as it is naturally produced and destroyed throughout the atmosphere.

13. Spectral Analysis (as termed by the author)

Greenhouse gases, such as water vapour, carbon dioxide and methane absorb infrared radiation at specific wavelengths, or "spectral fingerprints."

Analysis using spectral databases allow scientist to estimate values for one of the four parameters in the Schwarzschild equation, considered above – i.e. ‘the propensity to absorb at any particular frequency of radiation’.

The quantitative (theoretical) technique for estimating the incremental Greenhouse gas absorption from incremental atmospheric concentrations is referred to, in the books ‘Natural and Anthropogenic Climate Variability’, as ‘Spectral Analysis’. Generally, the term is used for the process of examining a signal to identify and quantify its constituent frequencies, revealing its underlying periodic components.

The term ‘Spectral Analysis’ may alternatively be called ‘radiative forcing’ or ‘effective radiation forcing’ calculations.

The ‘broadening’ modelled by academics in their theoretical calculations mainly use the HITRAN database which has data for each of the plethora of greenhouse gas spectral lines. Each line is characterised by 19 parameters (in 160 ASCII characters). Only two of these are relevant to the ‘broadening’ calculation.

The self-broadened (and the air broadened) ‘half width at half maximum’ represents the width of a spectral absorption line when it is broadened by collisions with identical molecules of the same gas (or by other atmospheric molecules – Nitrogen and Oxygen). This parameter is half the full width at which the spectral line's intensity is half of its maximum value.

These parameters are used to model how increased concentrations of GHGMs absorbs additional photons, as it quantifies the line's spread in wavenumbers due to collisions with its own kind at a specific temperature and pressure. In the 'broadening and overlap' zone the already complicated overlap of carbon dioxide and water is further coplicted by some other GHGMs overlapping.

Spectral Analysis is a technique which, although based on the fundamental science of vibrational absorption of infrared radiation by GHGMs, requires assumptions to be made in order to complete the calculation in a 'Real Skies' situation.

These assumptions vary according to the philosophical orientation of the researcher. In particular, it is the assumptions as to how all the parameters of the Schwarzschild radiative transfer equation’s parameters are dealt with. The only direct link from Spectral Analysis to the radiative transfer equation is to the ‘cross section’ parameter.

The debate revolves mainly around the concepts of Saturation and Overlap which are discussed in the text to which this section is referred.

Any analysis that starts with the assertion that ‘Anthropogenic emissions cause dangerous Global Warming’ will naturally result in proving the assertion to be true.

14. Arrhenius form Equation

First proposed by a Swedish chemist in circa 1900, the equation links rise in surface temperature to increased concentrations of GHGMs. For carbon dioxide this is

Temperature Rise = A * ln(CO2 in ppm) (ln: natural logarithm)

Although many modellers agree on this form of relationship, they disagree on the value of the constant ‘A’.

Currently the IPCC consider the most likely value for ‘A’ is 5.35. This gives the answer in watts per square metre which is further divided by 4.71 which is the conversion factor for Greenhouse Effect in watts per square metre to surface temperature coming from the total warming of the Earth’s surface being 33 to 34⁰C.

Various papers have been published including Zhong and Haigh’s 2013 paper: "The greenhouse effect and carbon dioxide” based on Spectral Analysis with conflation of the Schwarzschild radiative transfer equation’s parameters.

W. A. van Wijngaarden and W Happer’s seminal 2020 paper ‘Dependence of Earth’s Thermal Radiation on Five Most Abundant Greenhouse gases’ adopts a similar methodology to Zhong and Haigh but incorporates consideration of more of the Schwarzschild equation parameters.

15. W. A. van Wijngaarden and W. Happer’s 2024 paper (Clouds)

W. A. van Wijngaarden and W. Happer’s 2024 paper “Radiation Transport in Clouds” goes someway to putting a theoretical basis behind the effect of clouds – in effect taking into account that ‘Clear Sky’ conditions are rarely observed. Their paper highlights the complexity of the subject